NEWS

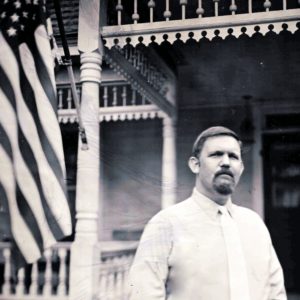

Brian Davis

Brian Davis loves old stories with happy endings.

In his profession as executive director of the Louisiana Trust for Historic Preservation, the 1997 Louisiana Tech architecture graduate tries to make that very thing happen as often as possible.

In his profession as executive director of the Louisiana Trust for Historic Preservation, the 1997 Louisiana Tech architecture graduate tries to make that very thing happen as often as possible.

“The reward is seeing a building on its last legs but knowing it has potential, then having a part in saving it,” Davis said. “One day you see cars parked out front of it again, children playing in the yard. You’ve helped bring it back from the brink, back to being alive again.”

He had a similar feeling as an architect. He’d meet with a client, understand the client’s needs and resources, then come up with a design to meet those needs.

“Eight months later,” he said, “you’re walking with your client through this ‘thing’ that started out only in your head.”

After leaving Tech, he worked as an architect in Houston and Galveston and got involved in preservation by volunteering to serve on historical foundation boards. He served on the staff of the Galveston Historical Foundation for eight years, got onto the board, then made the jump from architecture into the non-profit world in 2004 when he became Galveston’s Director of Preservation Services.

After leaving Tech, he worked as an architect in Houston and Galveston and got involved in preservation by volunteering to serve on historical foundation boards. He served on the staff of the Galveston Historical Foundation for eight years, got onto the board, then made the jump from architecture into the non-profit world in 2004 when he became Galveston’s Director of Preservation Services.

“I’ve always been interested in history,” he said. “Then this connection with buildings bridged the gap.”

For Davis, that equaled the best of both worlds.

He worked in North Carolina as executive director of the Historic Salisbury Foundation for three years before coming home to Louisiana in 2015, where the West Ouachita High grad works from the family farm in Ouachita Parish and leads an 18-member board whose members are spread out all over the state.

“Most of our meetings are by conference call,” he said. “We have quarterly meetings; in today’s world, a lot of our work is done through email. If anyone has a question about a building, no matter where they are in the state, we’ll have somebody on the board who is nearby and can help.”

Although the legal parts of preservation and the physical preservation of structures can be intricate, Davis feels his job, at its core, is simple: “I’m here to help people or communities find out how to do it,” he said. “All across the state, we have some wonderful buildings that are vacant and people who want to help see them restored. We’re looking for the ones that need to be preserved.

“Blight is everywhere,” he said. “Big cities are all about eliminating blight. But what’s happened to the building over time is not the building’s fault. And once you tear one down, the city still has that block to mow. Maybe the building can be saved, restored, and used for good. Part of my job is getting the community involved to restore these treasures.”

Unless the Foundation steps in to stabilize the buildings and make them watertight, history will disappear. Through use of a revolving fund and help from volunteers, the Foundation can acquire endangered properties, get them stabilized, then sell the building as a shell.

“Then we can save more money,” Davis said. “We can save two or three for the price of re-doing one.”

While in Galveston, Davis led the efforts to restore the Green Revival House, damaged by Hurricane Ike in 2008 and slated for demolition.

While in Galveston, Davis led the efforts to restore the Green Revival House, damaged by Hurricane Ike in 2008 and slated for demolition.

“We moved it to a new lot and did a complete rehabilitation to it,” Davis said. “It’s the first residential rehab in the country to get a Platinum rating in the LEED for Homes energy program (a ‘home energy efficient’ rating system).”

With the help of a grant from the Louisiana Department of Historic Preservation, Davis and the Foundation were able to acquire two buildings on Homer’s Historic Square that had been used for storage for the past 30 years.

“We were able to replace the metal roofs and paint the exterior of both buildings,” he said. “They are currently for sale and are eligible for state and federal rehabilitation tax credits, which could cover up to 40 percent of the rehab expenses. Once sold that money will ‘revolve’ back into saving more historic buildings across the state. We’re always looking for the next properties to save.”

The Foundation has four properties now but at any time can have as many as 10. Once a property is acquired, a community workday is scheduled for things like weed-pulling to improve the street presence.

“It allows people to be a part of saving something,” Davis said. “If anyone wants to get involved, all they have to do is contact us and let us know what they’re interests are. A lot of this happens because of community involvement.”

Each year at its annual statewide conference, the Foundation recognizes a “Main Street community,” a place that “exemplifies the strategic use of creativity, historic preservation and/or culture to build a climate for cultural expression, improve quality of life, enhance existing assets and strengthen economic opportunity while respecting the quality of the area.” Ruston won the award in 2018.

Each year at its annual statewide conference, the Foundation recognizes a “Main Street community,” a place that “exemplifies the strategic use of creativity, historic preservation and/or culture to build a climate for cultural expression, improve quality of life, enhance existing assets and strengthen economic opportunity while respecting the quality of the area.” Ruston won the award in 2018.

“Ruston had made the biggest turnaround and the most improvements,” Davis said. “These kinds of things happen with a lot of teamwork and vision over time.”

Davis had the unique experience recently of refurbishing his grandparents’ 1920 farm house, which is now his home.

“I was my own client for the first time,” he said. “I thought we worked well together.”

Recent Comments